Like the light of the sun, it beautifies all things on which it shines, and is no less welcome in the palace than in the humblest home. –Lewis Latimer

On the corner of 137th Street and Leavitt Street in Flushing, Queens stands a 19th century Queen Anne-style frame house that has not always been there. Its original location until 1988 was on Holly Avenue, just over a mile away, when the house was painstakingly relocated to avoid demolition. In 1995, this modest home was declared a landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee in recognition of the importance of its architecture and to honor the life of its former resident Lewis H. Latimer: inventor, draftsman, writer, and early advocate of civil rights in the United States.

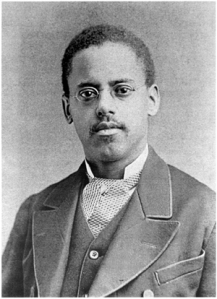

Born in 1848 in Chelsea, Massachusetts, Lewis H. Latimer’s contributions to the modern age remain largely unrecognized. A man of humble beginnings, he first discovered his talent for inventing while serving in the Union Navy. After his discharge in 1865, he returned to Boston and was hired by Crosby and Gould, a patent law firm seeking an office boy with a “taste” for drawing. Latimer watched the draftsmen of Crosby and Gould and soon was able to purchase his own tools and a second-hand book on drafting. He remained with the firm as a draftsman for 11 years. While working at Crosby and Gould, Latimer helped Alexander Graham Bell apply for his patent for the telephone, submitted on February 14, 1876, beating Elisha Gray to the patent by only a few hours.

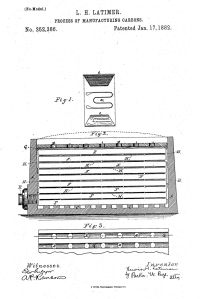

In 1879, Latimer moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut to join family, where he encountered Hiram S. Maxim, chief engineer of the U.S. Electric Lighting Company. He worked with Maxim for three years, and together their work was instrumental in advancing the field of electricity. They received patents for improvements in light bulb manufacturing and installed electric lighting in major urban centers, like Montreal and Philadelphia. In New York City, Latimer supervised the installation of electric lighting in the Equitable Building and the Union League Club, among others. During this time, Latimer received a patent that would eventually render incandescent lightbulbs practical for the average household by designing a new carbon filament that was long-lasting and affordable. This invention replaced fast-burning paper filaments and revolutionized artificial lighting, though Latimer is seldom credited for the role he played.

Technical drawing: Lewis H. Latimer’s Patent 252386 for the process of manufacturing carbons

(Drawing by Lewis Latimer, public domain)

For most of the remainder of his life, starting in 1884, Latimer primarily worked for Edison at the Edison Electric Light Company in New York, later to be known as General Electric. He served in the important capacity of chief draftsman of the legal department and as a patent investigator and expert witness for patent challenges. On Edison’s encouragement, Latimer authored Incandescent electric lighting: A practical description of the Edison system, published in 1890.

Equality before the law, security under the law, and an opportunity, by and through maintenance of the law, to enjoy with our fellow citizens of all races and complexions the blessings guaranteed us under the Constitution. –Lewis Latimer

During his years of service during the Civil War, Lewis Latimer witnessed the heroism and loyalty displayed by Black soldiers, leading Latimer to a deep belief in the fight for equal citizenship for African Americans under the law (Schneider vi). His own father George Latimer—a slave and the son of a white plantation owner in Virginia and a black slave—had been the focus of controversy when he and his wife fled slavery for Boston, which by the mid-1800s had become the center of the abolitionist movement. The controversy eventually led to George Latimer’s forced return to Virginia, and he was only freed upon the actions of the Boston abolitionists, who petitioned his case and paid $400 to George Latimer’s master for his release.

When Lewis Latimer first moved to New York City to work with Edison, he rented in Manhattan. As means provided, he later leased a house in Fort Greene, which in 1893 was one of the few middle-class neighborhoods with a substantial Black population at the time (Landmarks Preservation Committee 4). Latimer found he was able to buy a house by 1903, and he chose the neighborhood of Flushing, which was largely white, but by American standards had a sizeable African American population. Flushing High School, for example, had become racially integrated in the 1880s. His Flushing home became a meeting place for African American civic and cultural leaders. Latimer’s circle of friends included such pioneers in the struggle for justice as Richard Theodore Greener, Arthur Schomburg, and W.E.B. Dubois. In 1902, Latimer fought to restore the only African American member of the Brooklyn School Board, Samuel Scottron, who had been dismissed due to racist political pressure.

Latimer was a corresponding member of the Negro Society for Historical Research in New York City and his volunteer work included instruction in mechanical drawing and English to immigrants at the Henry Street Settlement. He founded the Flushing Unitarian Church in 1908 and was an officer of the local chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic, a Civil War veterans group. Lewis H. Latimer died in Flushing in 1928.

–Karen Li-Lun Hwang

Recent funding sponsored these Korean and Chinese translations of the wall text at the Latimer House. The House’s caretaker, artist Joel Colub, hopes soon more translations will follow to serve Flushing’s diverse population

(Photo Karen Li-Lun Hwang)

Suggested resources

Latimer Family Papers 1870-1996, at the Queens Borough Public Library, Archives at Queens Library.

The Latimer Family Papers collection is held at the Archives at Queens Library and is available for consultation by appointment. Spanning from 1870-1996, the collection covers the work of Lewis H. Latimer and the Norman family, particularly Winifred Latimer Norman, and includes correspondence, financial records, memorabilia, photographs, creative works, work records, and printed materials. It consists of 18.1 cubic feet held in 42 boxes, 5 binders, and is divided into four subgroups: the Lewis H. Latimer Papers; the Louise Latimer Papers; the Latimer Fund, Inc. Records; and the Latimer Norman Family Collection.

Finding Aid: http://digitalarchives.queenslibrary.org/vital/access/manager/Repository/aql:244/EAD

Latimer, L. H., Field, C. J., & Howell, J. W. (1890). Incandescent electric lighting: A practical description of the Edison system. New York: D. Van Nostrand Co.

Incandescent electric lighting: A practical description of the Edison system is a publication by Lewis H. Latimer from 1890, a seminal work on incandescent lighting, written by Latimer during his time with Thomas Edison. It is a scientific work that is 140 pages long, describing incandescent lighting at its earliest stage of development, with illustrations by Latimer.

Available online: http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015004960319;view=1up;seq=1

Schneider, J. M., Singer, B. S., Davis, A. J., & Manning, K. R. (1995). Blueprint for change: The life and times of Lewis H. Latimer. Jamaica, NY: Queens Borough Public Library.

Blueprint for Change is the catalog for the 1995 exhibition at the Queens Borough Public Library to showcase their Latimer Family Papers collection. The 86-page catalog includes extensive illustrations and photos, as well as original texts by different authors, covering various aspects of Lewis Latimer’s life, such as his work as a civil rights advocate, his inventions, and his career.

Available online: http://digitalarchives.queenslibrary.org/vital/access/manager/Repository/aql:51/SOURCE1

References

Landmarks Preservation Commission. (March 21, 1995). Lewis Latimer House [report]. New York: Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Lewis H. Latimer House. Permanent Exhibition. Flushing.

Schneider, J. M., Singer, B. S., Davis, A. J., & Manning, K. R. (1995). Blueprint for change: The life and times of Lewis H. Latimer. Jamaica, NY: Queens Borough Public Library.